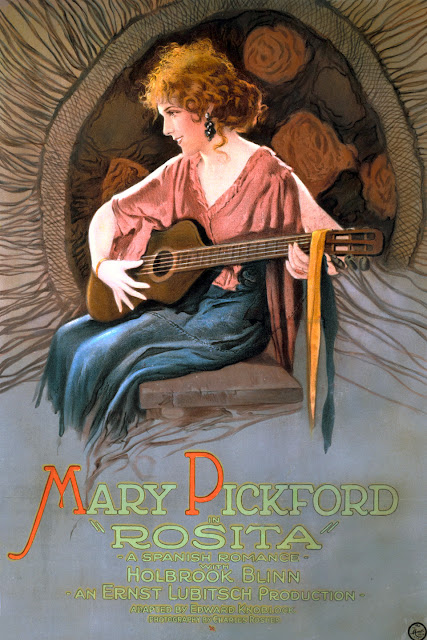

The Museum of Modern Art, with cooperation from the Mary Pickford Foundation, has restored Ernst Lubitsch’s Rosita (1923), starring Mary Pickford, from the last known surviving nitrate print found at Gosfilmofond in Russia. The Pickford Foundation provided access to our 35mm elements and The Film Foundation and The Mayer Foundation also cooperated with MoMA on the restoration.

Rosita had its restoration premiere during a “pre-inaugural evening” before the Venice Film Festival on August 29, and it will be wonderful to have the film (and the original orchestral score they are recording for it) available to audiences again.

A variety of stories have grown up around Rosita over the years; in fact, the Venice press release says, “The film was, by all accounts, a major critical and commercial success on its first release, but in later years Pickford turned against it, for reasons that still remain mysterious.” Actually, the story isn’t really “mysterious” at all, but is nuanced and a bit complicated, so this seems as good a time as any to revisit Rosita and Mary’s thinking about it.

Before even getting to that, however, it is important to note that it was Mary Pickford who brought Ernst Lubitsch to America in the first place, and, in 1922, that was no small feat. World War I had just ended and Americans who had been inundated with anti-German films and urged to “Come and Hiss the Kaiser” were not in a forgiving mood. Mary herself had ended her 1918 film Johanna Enlists with the proviso, “Don’t come back til you’ve taken the Germ out of Germany.”

Pickford had seen Lubitsch’s German films and was impressed. As she recalled in a 1958 interview with George Pratt, “I had already done the second Tess of the Storm Country and I wanted to do a grown-up role. I wanted to do an adult woman.” And she thought a director such as Lubitsch would have the “touch” to do that successfully.

But first she had to get the director to Hollywood, and the American Legion (among others) objected vociferously. Pickford recalled to Kevin Brownlow in 1974 that she was on stage when the head of the American Legion took to the podium to say: “I hear that the Son of the Kaiser is coming here. He doesn’t belong here, he is still our enemy. Why are they bringing German singers over here? Do we not have good enough singers here in the United States, without going to Germany?”

Pickford’s response: “General. Since when has art had borderlines? Art is universal. And for my pictures, I will get the finest, no matter what country they come from. The war is over. And it’s very ill-bred and stupid for the general to stand up and talk like that. A German voice is God-given if it’s beautiful. Yes, I am bringing Mr. Lubitsch over here and I’m glad I can.”

Pickford, who appreciated her power yet was careful about how she used it, had stood up for what she thought was right. Still, the woman who had put her career on hold to tour the country and sell millions of dollars in war bonds said she found herself being denounced as a traitor for ignoring our own directors in favor of the erstwhile enemy.

Pickford also told amusing (in retrospect) tales of getting Lubitsch off the ocean liner and eventually to Hollywood safely and with a minimum of publicity. The plan had been for him to direct the film Dorothy Vernon of Haddon Hall. He had read the script in German and had agreed, but once in Hollywood, he decided he didn’t like the story and insisted on doing something else.

Lubitsch next suggested Faust, and in retrospect Mary said she wished she had done it, but before that got off the ground, Mary’s mother Charlotte asked the director about the story. According to Mary, the conversation when something like this:

Lubitsch: “Yeah, she has a baby, she’s not married, so she strangles the baby”

Charlotte: “What? What was that?”

Lubitsch: “She has a baby, she’s not married, she strangles the baby”

Charlotte: “Not my daughter, no sir!”

As Mary summed it up, “And so I didn’t make Faust.” (Brownlow)

Mary was always happiest when she was in preproduction, production or even post production. But since Lubitsch had arrived, she had been in none of these and was starting to get anxious. She had gone out on a limb to bring him to America and she wanted to get to work. Finally, they compromised on a story about a young Spanish maiden caught in court intrigue in the late 1880s, loosely based on a French opera. Eddie Knoblock wrote the script for the romantic drama and the art director, William Cameron Menzies, went to work recreating Seville, complete with a castle and cobbled streets, all on the Pickford Fairbanks lot on Santa Monica Boulevard.

Initially, Mary was comfortable with the essence of her character, a strong-willed young woman with principles and a backbone, who supports herself and her family as a street singer. In fact, at first, that was the film’s working title: The Street Singer.

Part of what Mary wasn’t comfortable with was the flirty nature that Lubitsch wanted her to exhibit. They were both very strong-willed people, set in their ways, and had more than their share of conflicts about the story and Mary’s performance, but Pickford said she was always careful to have those discussions in private.

Mary told the story of how, early on, she and Lubitsch had a disagreement about the way the love story was developing and she visited him in his office:

“Mr. Lubitsch, this is the first time you’ve met me, as the financial backer and the producer.”

He said “Vot is this?”

I said “I am telling you that I am the court of the last appeal.”

“Vot is this?”

I said “I’m putting up the money, I’m the star, I’m the one that’s known, and you are not going to have the last word.”

Lubitsch was used to being in charge and having a star who was also the producer was a new and disconcerting experience for him. While Lubitsch’s command of English was still in its formative stages, Eddie Knoblock spoke excellent German and could be called on to clarify any misunderstandings.

In later years, Pickford reflected on her experience being directed by Lubitsch in Rosita. “Of course, the director can be as much miscast as an actor,” Mary mused during her oral history for the Butler Library at Columbia. “For instance, take Lubitsch directing me. Now of course he understood Pola Negri or Gloria Swanson, that type of actress, but he didn’t understand me because I am purely Americana. I’m not European. Just as John Ford I don’t think could direct Negri.”

The bottom line was while Lubitsch saw himself trying to get Pickford out of her comfort zone as an actress, she felt he was asking her to play a character she eventually found to be one-dimensional. Pickford tried to explain the give-and-take she experienced with Lubitsch to George Pratt. “Being a European, he liked to do naughty and suggestive things. He tried to be as moral as he knew how and I tried to be slightly naughty. And I have always thought,” she said with a laugh, “that the result was pretty terrible.”

She was speaking as an actress about her own performance, however, and when she put on her producer hat, she admired the film. She found “that the costuming, the décor and the sets are magnificent and so was the photography [by Charles Rosher].“ And then she added, “I just didn’t like myself as Rosita and I think it was my fault and not Lubitsch’s.”

So Mary’s feelings aren’t so mysterious after all. And the current restoration of Rosita allows us to see the film ourselves – Pickford’s performance, Lubitsch’s direction, Rosher’s cinematography, Menzies’s sets and all the other aspects of this 95-year-old film, thanks to MoMA and all the artists, archivists and funders who made this possible.

Republished with permission of the Mary Pickford Foundation

Photographs courtesy of:

Joseph M. Yranski

Bison Archives

The Academy of Motion Pictures Arts & Sciences (Mary Pickford with Ernst Lubitsch photo)

Photographs courtesy of:

Joseph M. Yranski

Bison Archives

The Academy of Motion Pictures Arts & Sciences (Mary Pickford with Ernst Lubitsch photo)

You can contribute here to help fund this event. Tickets will be for sale on Fandango.

No comments:

Post a Comment